A lot of people read books. A lot of people like books. A lot of people own books. Not all of those are my people: "book people" — people who love and revere books and all they stand for.

Every summer for twenty years, my Dad loaded my sister and me into a rented cargo van to make a pilgrimage from Houston to a parking lot in suburban Chicago. It was a pilgrimage because my Dad is a bookseller who loves and reveres books and all they stand for. Bookselling is his vocation. And in the latter half of the 20th century, if you loved and revered books and all they stand for, that parking lot in suburban Chicago became a holy site for two weeks at the beginning of every June.

We spoke of the parking lot often in our house. We planned our life around it. However, we rarely spoke about it openly to others. They wouldn’t have understood. The people in the know simply called it, “Brandeis.” It began as a simple idea: a school’s alumni network decided to gather donated books and resell them to raise money for scholarships to their alma mater:

Since its beginnings in an empty storefront in Winnetka back in 1959, the sale has brought in more than $1 million to support the libraries at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass. The university housed its first library in a converted horse stable. One of the university trustees suggested that women around the country get involved in efforts to raise funds for the library.

Chicago Tribune, 1994

Alumni chapters all over the country organized sales, but none approached the scope or influence of the Chicago chapter’s perennial summer sale. It was more than an event — it was commerce, congregation, and circus all in one. When we said Brandeis, there was no confusion about where we were going. But to stop at calling Brandeis another used book sale would be like calling the Forbidden City another house, or the Vatican another church. It was a fixture in my life as well as in many others’, not least of which my father’s. And to recall it is to understand why I became a writer, and why I believe what all those pilgrims believed: that civilization lives in books.

On The Road

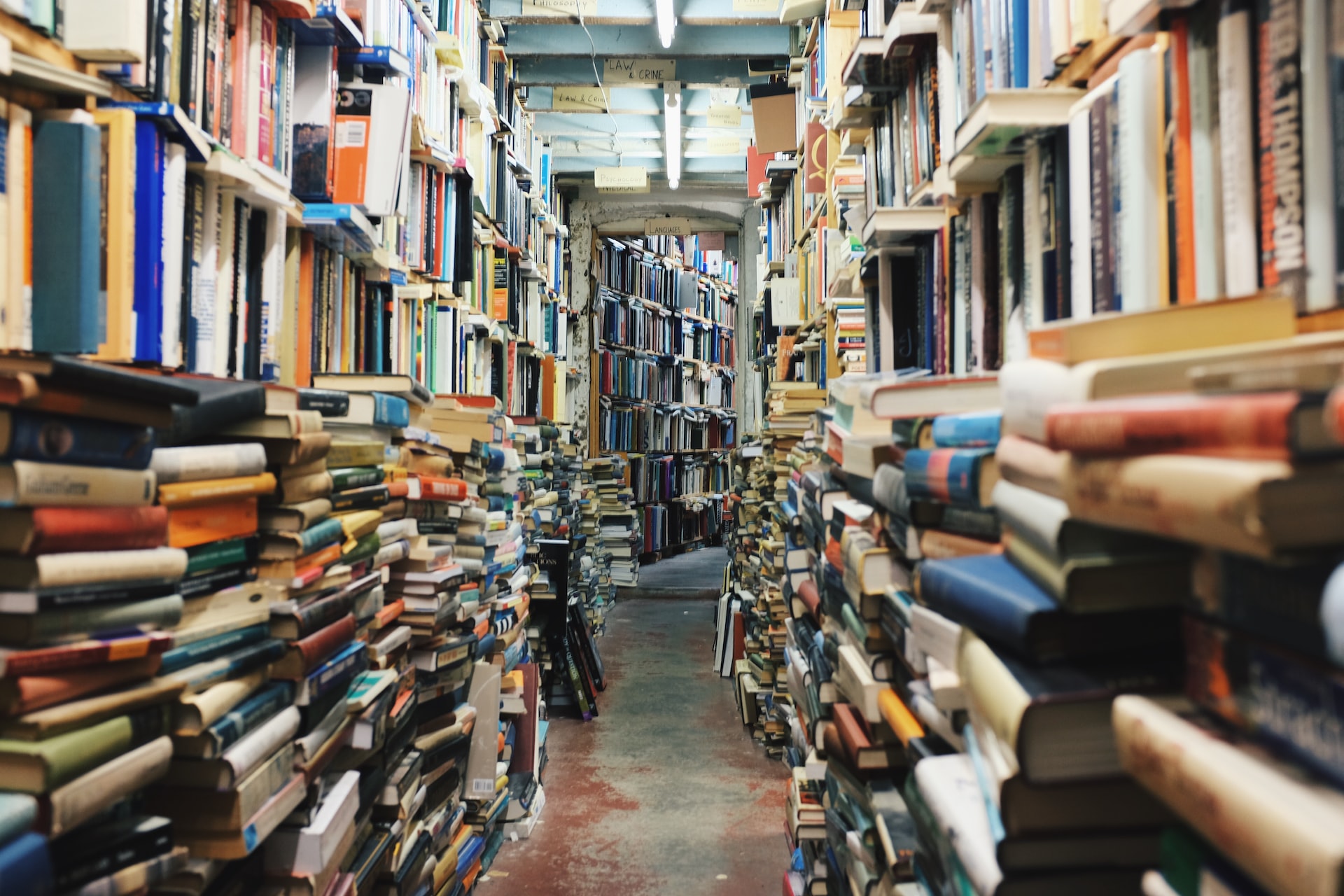

To my Dad, the bookstore was a home, a business, and a job, but beyond any of these, the bookstore was his vocation, a sacred calling. For most of my childhood, he had a monastic morning routine, waking up at almost 4:00 am to have a cup of coffee (with copious powdered creamer — never liquid creamer and never any sweetener), then reflecting silently in our living room. After this period of reflection concluded, he would print all of the orders people had sent in, and walk silently through the stacks and shelves for hours, pulling books off the shelf, then saying a silent benediction over each one as he fastidiously folded the order paper, slipped it inside the front cover, and stacked the books together to be packaged to ship or prepared for in-store pickup.

Because my father was a bookseller, my childhood was made of books. My Dad would often tell people that a book they wanted was stored at our warehouse. This “warehouse” where books were stored was actually just the house that we lived in (that my parents still live in). Counting the garage, there are nine rooms. At any given time, four or five rooms featured bookshelves as the chief decoration. Recently, for the first time in over twenty years, my Dad has cleared enough out so that only two rooms are so full of books that you cannot walk into them. (To my knowledge, this is a feat he hasn’t managed since they moved into the house in the 1980s.)

As much as my Dad revered books, he was also a businessman. He was a master of rare-book arbitrage. Although there are garage sales and secondhand shops where we live in Houston, the likelihood of finding a 100-year-old book is slim. That’s because unlike his hometown, Chicago, Houston has a salty, hot climate that is hard on books. Air conditioning only became mainstream around the 1950s, and Houston’s population didn’t explode until the 1980s when my parents showed up with all the other transplants. When he moved here, my Dad opened his secondhand bookstore in a sleepy suburb of West Houston. He did well in sales but sometimes had trouble stocking valuable used books. That’s why we would drive across the country every year: to buy as many high-quality used books as possible.

Every June in the week before Brandeis, the Becker household had “hurricane energy,” that subtly manic atmosphere that you might encounter in a grocery store days before a natural disaster is predicted to hit the area. After school would let out for the summer, my Dad would start making preparations like finding a van to rent. He would also start the weeks-long discussion with my Mom about whether she would come to Chicago with us or not. This discussion was like a prolonged chess match performed in the style of a tango, highly stylized and alternately furtive and heated. My Dad wanted us all to go, but my Mom resisted. She would end up coming with us about half the time.

My Dad would insist that we put our bags in the van the night before and wake up tremendously early, sometime between 3:00 am and 5:00 am, so that we could “make good time” on the eighteen-hour drive to Chicago. According to one of his legendary idiosyncrasies, he would throw together whatever leftovers we had between hamburger buns, and say, “Alright — we have sandwiches, don’t need to stop for food.” Before lunch, the grocery bag or other similarly unsuitable container would transform into a goulash of leftovers and wet hamburger buns. Eventually the mountainous, immovable object of my Dad’s resolve to “make good time,” would crumble under my sister’s relentless river of requests to stop at Arby’s somewhere in East Texas or Arkansas.

Unlike the provided lunch of lukewarm, grocery-bag sandwich stew, the in-car entertainment was enviable. Around when I was eight, my Dad found out he could use an AC adaptor to power appliances through the van’s cigarette lighter, so he duct-taped a TV/VHS combo to the floor between the two front seats. My sister and I would then argue about which movies to watch on the drive, inevitably compromising by watching every single one she wanted to watch and none of the ones I wanted to watch.

Sometimes, my sister would pinch or scratch me, so I would draw on her legs, arms, and — when possible — her face with colored markers. We would show up to Chicago looking like wild animals, covered in cheap markers, scratch marks, with a little blood here and there. My Dad would try to stop us, but he didn’t care much what we did or what we watched. He was focused on the drive.

There was a deep intention to our journey. Even when I got older and would sit up front with him, he would only talk to me if I engaged him. Otherwise, he would drive in silence, not even wanting to listen to music.

Great Expectations

On the first day in Chicago, we got up early to scope out the tents the day before the sale opened. They were massive yellow-and-white-striped circus tents, nearly three stories tall, that contained over 40,000 square feet of hallowed ground. For a few weeks once a year, the tents were unmistakable landmarks taking up most of the parking lot in the aforementioned suburban mall. In 1994, the Chicago Tribune called the tents the “harbingers of summer.” On the first day of the sale, they opened the tents at 6:00 pm.

Nearly 2,000 people would wait in line for up to twelve hours and also pay an admission fee in order to get a first look at the books. My Dad had been coming to Brandeis for decades before I came to my first one. We would get chairs and wait outside the tent, baking in the summer sun. Sometimes my Dad would give us ice cream or something similar, but often we would just sit there, dehydrating in sticky folding chairs.

Among the people waiting outside with us were a lot of other booksellers. Every person in line was at least a book collector. People came from all over the country (and farther) and rearranged important parts of their lives to make sure they could get to the sale on opening day.

One man ducked out of his son’s wedding reception to come to the sale . . . He showed up here in a tux. And this year we got a call from a man who was upset because he had scheduled his two-week European vacation on the assumption that the sale would be over Memorial Day weekend. When he found out it was the next weekend, he called to see if we could change it back.

Chicago Tribune, 1984

These people waiting outside the tent were my people: ”book people.” A lot of people read books. A lot of people like books. A lot of people own books. Not all of those people are book people. I grew up around book people. They love books, but are otherwise hard to categorize. They lean introverted, but you will meet some serious talkers too. They are more often cerebral and intellectual, but many book people read books for the passion, or the excitement, or the escape. What separates book people from others is that they regard a book as more than the sum of its parts. Once the words are down and the book is printed, something special happens, and the book ascends to a new dimension of meaning. It would be a mistake to think of book people simply as enthusiasts, the way you would other collectors or hobbyists. Particularly with the type of book person who showed up to Brandeis, there are better words to describe them: acolytes, adherents, devotees, fanatics.

I learned a lot about the world sitting in that line. Some people were there for the mysteries, or to collect the work of a specific author, like William Butler Yeats, or Zora Neale Hurston, or Edgar Rice Burroughs. Some people were there for a specific genre, like mystery or history. Often, I’d meet someone who wanted to collect books about their community. I met people who were looking for women authors, Black authors, Latino authors, and gay authors. Each time someone told me they were there to collect a specific type of book, I would try to kill time by following up to ask about it. Asking “what are you here for,” and simply listening to the person passionately explain why they wanted to wait in the hot sun all day, my mind would open to whole new universes of people and ideas.

There were exceptions, obviously. Occasionally someone would be collecting books on the occult or erotica, and they wouldn’t want to talk to a ten-year-old about it. Once, there was a gentleman with no hair on his head but a large ponytail who took a particular distaste to my sister and me being in line. Another time, there was a very dapper, polite old gentleman who was keen to make conversation but would not tell us anything about himself until we asked why he talked the way he did, at which point he said he was from another country. My sister and I then started a three-hour guessing game where we said every country we knew, and he would say, “ah, sorry, zat eez naht eet.” Until finally we gave up, and my Dad guessed Latvia — which was it! Latvia was the star of our conversations on the drive home and for weeks afterwards, with us trading facts about Latvia, wondering what it was like, and imitating our new-found Latvian friend’s accent.

The old Latvian man was just one of many memorable characters. As much as we were there to crowd the tents and adore the books, it was the people who made it Brandeis.

Sense and Sensibility

Some of these people would show up once and never again, but others would be there year after year. One constant group was the women taking the admission fees and opening the tents. They were volunteers from the North Shore chapter of the Brandeis University National Women’s Committee, who ran the sale for almost sixty years. They were all the age of my grandparents, members of the “Greatest Generation” that lived through World War II. Many of the patrons were of that same age, including the Latvian charmer and other people who would stop to make conversation with him or some of the volunteers.

The volunteers, who were mostly older women, were what made the sale the perennial powerhouse it was. One uncharacteristically hot year, when I was about eleven years old, I noticed a woman moving among the customers and volunteers who had a crudely drawn tattoo of some numbers on her forearm. I asked my Dad what the tattoo meant, and he said he would explain it on the drive home. Just a bit later that afternoon, waiting for the tent to open on the first day, the Latvian charmer gently stepped in to answer some of the questions he’d heard me ask my dad. He told me what the tattoo likely meant, and pointed out that someone with that tattoo may have been in Germany to see the Nazis burn piles of books as big as the Brandeis tents. He was also the first to tell me that Jews are sometimes called the “people of the book.”

Brandeis University was founded shortly after World War II to be the premier Jewish university in the world at a time when other schools had restrictive Jewish quotas. All over the country, alumni collected donations of books and resold them as a way to raise scholarship money for future Brandeis students. Not only was the one in Chicago the largest sale of its kind in the country, but the inventory was fresh every year. After the sale, they would donate the leftover books and start over. Over 400 volunteers would work all year to collect and sort over half a million books. It was a marvel to behold.

That the North Shore chapter of that national women’s effort became the most successful is partially due, says volunteer Katz, to [Brandeis University’s] first president, Dr. Abram Sacher, being head of the Jewish Hillel at the University of Illinois, and he was dearly loved by his former students, many of whom had settled on the North Shore. When he became president of the new university, his former students vowed to do anything they could to help him and Brandeis.

Chicago Tribune, 1994

The volunteers and our friend from Latvia were the best of the book people — warm and welcoming but stern if needed. The day we talked, the old man from Latvia gave me a lesson in history and tact. For every question I asked, he gave a thorough answer in a slow, kind, measured tone. He would occasionally quiz me on small facts he had told me earlier. It felt serious, like a sermon, something that I needed to guard and give to the right people later. The gravity of the conversation contrasted us sitting in cheap lawn chairs outside a giant yellow tent in a mall parking lot.

There were usually four tents: one small tent, two large tents, and one enormous tent. Inside the tents were long picnic tables that had books stacked on them, spine up, so you could read the name of the book and the author. The books had been sorted beforehand, and the tables were organized by genre. On the first day, this did not matter as much to my sister and me. We would normally end up at the Children’s book sections, or the art and photography books.

The opening of the tents was like a running of the bulls. People would be pushing their carts at full speed, demolition derby style. My Dad had a special calculus he used for that first day. I never saw him run, but I saw him walk faster in those tents than I ever saw him walk anywhere else.

The Things They Carried

My Dad wore thick-frame glasses and a short-sleeve polo or button down. He followed a ritual similar to many others. He would briskly walk to a table and then stand above it, scanning across rows of books with his index finger, picking up every tenth book or so to inspect it, putting one of every three or four books he picked up into a cart. In this fashion, he would go through a table in a few minutes, and fill up three or four carts in an hour.

There was a dramatic change in the energy from just minutes before outside the tents. Like concert-goers that have been stuck, ambling in a crowd for hours until they get to their seat and the show begins, the hot, tired, frazzled energy of the sale-goers would dissipate as the lights came up and the show began: the books!

This was no rummage-sale. Inside was religious, a place of relics and rituals. It’s hard to describe how many books there were and how good the books were. Old school Chicago book dealers had volunteered to sort the books for the sale, but with half a million books, even a dozen part-time volunteers could only sort a small fraction of them into the high-value areas. So you were likely to find something great if you knew what to look for.

As prickly and eccentric as they could be, the Brandeis attendees’ deep belief in the transcendent nature of the books meant that volunteers and shoppers alike would tolerate a lot of non-standard social behavior. Halting a conversation suddenly to break into brisk walking or muted jogging was acceptable — everyone understood you just wanted to see the books. Each devotee would hurry up and wait. They would run or speed-walk their cart to the tables then gingerly go book by book to see what they needed. The only real transgression against the divine law of the tents was impeding others’ access to the books. The minor form of this was conspicuous slowness, like jamming up walkways, or leaving your cart in front of a table. This could be absolved with a simple “sorry.”

But the cardinal sin of Brandeis was selfishness. Occasionally someone would run in on the first day, swipe all the books in one category into their cart, and then huddle with their cart in the corner like an altar boy drinking communion wine. This was a sin. And it was common enough that the volunteers dealt with patrons in a rather brusque manner; they were ushers and security guards, not so much customer service representatives.

When I got a little older, my Dad would start to let me in on some of the secret knowledge: “If you’re in mysteries, Ed McBain wrote a bunch of books as Evan Hunter, and Agatha Christie did the same thing as Mary Westmacott.” My Dad could watch someone shop and tell whether they were a bookstore owner, a book scout, or a book dealer. Bookstore owners were like him: surgical on the first day, then intentional but much less discriminating on the last day, when books were priced as low as $0.25 apiece. A book scout was a fairly knowledgeable person who worked for someone else. Sometimes they had one boss and sometimes they had two or three clients, and their job was to look for the specific type of books that their employer(s) wanted.

Book dealers were different. Some of them acted as scouts for themselves, looking only for specifics. But others had a direct connection to the main line. In Islam there is a person known as a hafiz, someone who has memorized the Koran. They are revered for their abilities and their knowledge. To book people, book dealers served a similar role. They had memorized some directory or card catalog the rest of us didn’t have access to. They had categorical knowledge of every book in every tent, where it was from, why it was valuable, and whether it was a good deal or not. My Dad started as a book dealer but he said there were others who far surpassed him in skill and knowledge. He counted some of these book dealers among his best friends (and most touchy frenemies) after running into them over and over for decades at Brandeis and other, lesser sales. I would always see them, moving a little more slowly over the books then everyone else. Then by the time we got to the last tent with our overstuffed carts, I would spy and eavesdrop on what they had bought.

After all the reverence and raucousness of the tents, we would conclude our religious observance with communion at a local restaurant called Hackney’s. We rarely ate out in Houston, and we never ordered appetizers, so it was always a huge treat when my Dad would order an obscenely large fried onion loaf to split. We would all dig in and give thanks for the books we found and that the sale was over.

The drive home was always much quieter than the drive there. First of all, my sister and I had less room to bicker and fight. Every square inch of the van was always packed. But beyond that, we would be exhausted from the fanfare of working. And the times we were awake, our heads were buried in one of the dozen or so books my Dad had let us buy.

Back in Houston, I had the same problems as any other kid who wanted to fit in but came from an excessively observant religious family. I found it difficult — sometimes fun but sometimes uncomfortable — to explain the literary artifacts in my house like stacks of boxes of books. I had trouble explaining the weird chores I had to do. (My friends came to call moving a few boxes stuffed with books the “Charlie Friend Tax.”) Mostly, I had trouble explaining why we went on this trip — why we made the pilgrimage — and why it was so important.

Things Fall Apart

As an adult, the closing of the sale in 2006 coincided with my graduating from high school. Many of the women who ran the Chicago event for five decades were getting too old to volunteer. Their children all had jobs, and the number of employees they had to hire to replace the volunteers cut into the profits of the sale. In the mid 2000’s, the sale changed hands from the Brandeis University alumni group to another group who ran it differently and didn’t have the social connections to muster up a similar deluge of books or recruit the volunteers to sort them. After a few years, the tent flaps closed for the last time.

In my mind, Brandeis still looms large. For all of my childhood, it was a Vatican or Mecca for people who loved old books, who treasured the written word. When I began research for this story, I was shocked how little had been written about Brandeis. Aside from an article or two about the final years of the sale, almost everything written about it was a profile in local Chicago papers — the kind of one-off story about “things happening in town this weekend.”

There was nothing about the hope, the poetry, the idiosyncrasy and practicality of this massive, uniquely American sale where book people gathered in a parking lot once a year for half a century to worship at the altar of the written word. There was nothing of the weirdness of the people who would rush to wait, skipping other serious obligations or rearranging their lives just to get a look at the books. There was nothing about the oddballs and culture clashes in the parking lot outside the tent every year, waiting to get their turn for the adoration. So, I set out to write this, to capture what I could, and to share why it was important.

To my father and the rest of us book people, books aren’t meaningful; they are meaning itself. They are how we record what matters, put it in something we can cherish, and save it for posterity. Civilization lives in books.

If love of books is a religion, my father is still a high priest. He works six days a week in his secondhand bookstore. At one point, much of the store’s inventory had been amassed through the annual pilgrimage we made to Brandeis, although it’s probably turned over several times by now. While I still practice, I’m not as observant as my father. I do plan to take over the store someday, and be there when people wander in and say the type of things I used to hear at Brandeis:

“Wow, there are so many books in here.”

“I didn’t know there were places like this anymore.”

“I could get lost in here.”

“I’m so glad there are still places like this around.”

I plan to raise my children to love books and keep the bookstore open as long as I can. But for now, the way I practice my love of books is to write the important things down. And so it is with sorrow and gratitude that I conclude this recollection of something that was once great and deserves to be remembered. For fifty years people from all over the United States gathered to trade cash for old books inside some circus tents outside a mall, because they cherished the written word, because some things deserved to be preserved, because they believed civilization lives in books. And all of these things are still true. Amen.

Charlie Becker is a Write of Passage Cohort 8 alumnus and mentor. He writes the Castles in the Sky newsletter, where he publishes essays and short fiction.